ANOTHER PLACE

Scrum binding, 64 pp, 209 x 297mm

30 black and white and colour photographs

Text by Emily Andersen

Produced and designed by Yukitomo Hamasaki (mAtter)

Published by LOWW.Co.Ltd, 2023

Edition of 300

PORTRAITS: BLACK AND WHITE

Anomie Publishers, 2018

Hardback, 120 pp, 230x180mm

70 black & white photographs

Texts by Emily Andersen and Jonathan P. Watts

Designed by Melanie Mues

EDITION OF 600

LIMITED EDITION OF 50 (SIGNED, NUMBERED + ORIGINAL PRINT): £150

AVAILABLE IN BOOKSHOPS OR DIRECTLY FROM EMILY ANDERSEN

PARADISE LOST & FOUND

Hotshoe Publishers, September 2009

Hardback, 84 pp

41 black & white and colour photographs with the contribution of Gabriela Switek

EDITION OF 750: £20

LIMITED EDITION OF 50 (SIGNED, NUMBERED + ORIGINAL PRINT): £150

AVAILABLE IN BOOKSHOPS OR DIRECTLY FROM EMILY ANDERSEN

SUPPORTED BY THE NATIONAL LOTTERY THROUGH THE ARTS COUNCIL ENGLAND

"EMILY ANDERSEN CAN PHOTOGRAPH THE DERELICT INDUSTRIAL RUIN AND MAKE BEAUTY OF IT. SIMILARLY, SHE PHOTOGRAPHS THE MOST SIMPLE GARDEN ALLOTMENTS THAT OTHERS IGNORE AS THEY HURTLE IN A TRAIN FROM BERLIN TO LEIPZIG OR WEIMAR... AND PRESENTS THEM AS EARTHLY PARADISES FOUND."

Bill Kouwenhoven, Berlin, July 2009

2018 Feature in Royal Photographic Society Journal, In Focus, Volume 158, November

2018 Press for Portraits: Black and White by Pelham Communications Art PR Agency, London and New York.

2018 Robert Elms interview BBC Radio London 94.9 (October 19 at 10.30)

2018 Hunger TV Magazine, October

2018 Widewalls interview, October

2018 LeftLion interview, November

2018 Association of Photographers interview, September

2018 Nominated for RPS 100 Heroines by the Royal Photographic Society.

Daniella Shreir, founder and co-editor of film journal Another Gaze, writing about Somewhere Else Entirely 3-channel portrait film, March 2023

A three-channel portrait film about the poet Ruth Fainlight

"Will it be a man, will it be another woman, will it be myself?" poet Ruth Fainlight asks in the voice-over of Emily Andersen's eleven-minute three-channel portrait film, 'Somewhere Else Entirely'. She is referring to the notion of the "muse" and although it is not made explicit, this three-part question is one Fainlight first posed in reply to an interview at an earlier point in her career; one she is – aged ninety at the time of filming – now reflecting back on.

Of course, the history of art has never cared to trace the figure of the muse in relation to the woman artist, largely because the latter has never been historicised properly, let alone mythologised. As art historian Penny Murray has it: 'Man creates, woman inspires; man is the maker, woman the vehicle of male fantasy.' Fainlight – a self-proclaimed feminist – nonetheless seems surprised by the confidence of her younger self: 'At that time I said arrogantly, "My muse is myself."'

There is something refreshing about 'Somewhere Else Entirely' in its relationship to the figure of the woman artist and constellations of influence. Now, of course, it is much more common to talk about influence than muses, and to tack this abstract, ineffable notion onto real figures. We can see this in our contemporary neoliberal feminist moment, in which the culture industries are excavating women "pioneers," and giving them their (rightful, although sometimes cynically delineated) places in museum and gallery exhibitions, on the lists of publishing houses, and in film programmes.

'Somewhere Else Entirely' might have represented an attempt to highlight Fainlight's importance qua woman poet or have used the film form as a vehicle through which to recast Fainlight as a neglected "icon" in her field (and Andersen certainly knows how to capture these, having taken portraits of women including Dame Zaha Hadid, Nan Goldin, Nico, Tracy Chapman, Helen Mirren and Whitney Houston across four decades as a photographer). Instead, there is a fundamental humility to the film on the part of both filmmaker and subject. Fainlight appears on-screen in her local park and at her home in West London. She prunes her houseplants, spins salad leaves, boils an egg, sorts through her papers, reads – and yes, writes. As well as being the elements that make up a life, these quotidian fragments make sense when read alongside her poetry. As Richard Carrington has it: '[Fainlight] finds strangeness and even mysticism beneath familiar surfaces. Domestic life often contains and reveals the most significant truths.' Meanwhile, Fainlight's voice, off screen, is edited into a monologue, and although it is obvious that she has been guided by Andersen's questions (at times I think I can make out a non-verbal utterance that seems to come from the filmmaker) her speech feels unprompted.

The first few seconds of 'Somewhere Else Entirely' plunge the viewer head-first into a psychoanalytical drama. On the middle screen, the poet appears at the end of a corridor and walks slowly towards the camera, as we hear on the voice-over:

"I'm alone in the house and suddenly feel

the need to phone my mother.

But it's decades since she died – and I don't remember having this urge before…"

From the depths of the dream-world, Fainlight's voice brings us into the concrete and pragmatic with a start. We realise that she has been quoting the first line of one of her poems ('A Meeting with My Dead'), and instead of unpacking or analysing it, she begins to discuss the shaping of its form. Andersen, meanwhile, cuts away from the corridor and to several annotated pages. Fainlight's hands gesticulate above them. "I'm already reaching the place of not knowing what I'm going to write next," she says. And a few moments later: "I only know what the poem is going to say when I'm writing it". Throughout 'Somewhere Else Entirely', Fainlight hovers above and circles her practice, sometimes capturing the inability to describe how a poem is made: "I only discover what I'm going to say while writing it", at others admitting her powerlessness: "I'm in the hands of the poem".

'Somewhere Else Entirely' is the product of a coincidence. Alongside her photographic practice, Andersen teaches at Nottingham Trent University. During a train ride back to her London base in 2011, she came across a review of Fainlight's New & Collected Poems, accompanied by a picture of the poet. Andersen realised she had seen this woman in her neighbourhood and took a clipping of the review. The next day at her local market, Andersen saw Fainlight and approached her with the proposition of a portrait. In Andersen's telling, Fainlight wasn't immediately convinced but emailed Andersen a few weeks later. A portrait was taken, a friendship emerged and then, over the following decade, a filmic portrait. The film represents an encounter in the longue durée, which seems pertinent to Fainlight's practice, in which she can spend "months or even years" on a single poem. Nevertheless, the initial, delicate meeting between the women is, I think, detectable in 'Somewhere Else Entirely' whose visual montage is shaped by Fainlight's narration. At no moment does it seem as though the filmmaker is bending the poet's words to her aesthetic desires. In its form, it is as though Andersen has taken Fainlight's practice as a cue for her moving portrait.

Daniella Shreir

2023

Claire Loughheed, Executive Director at Dundas Valley School of Art, Ontario (Canada), August 2016

"There is something in Emily's work as if the world holds its breath while she takes the shot. The absolute stillness is both serene and unnatural."

Sue Steward at The Arts Desk, 2009

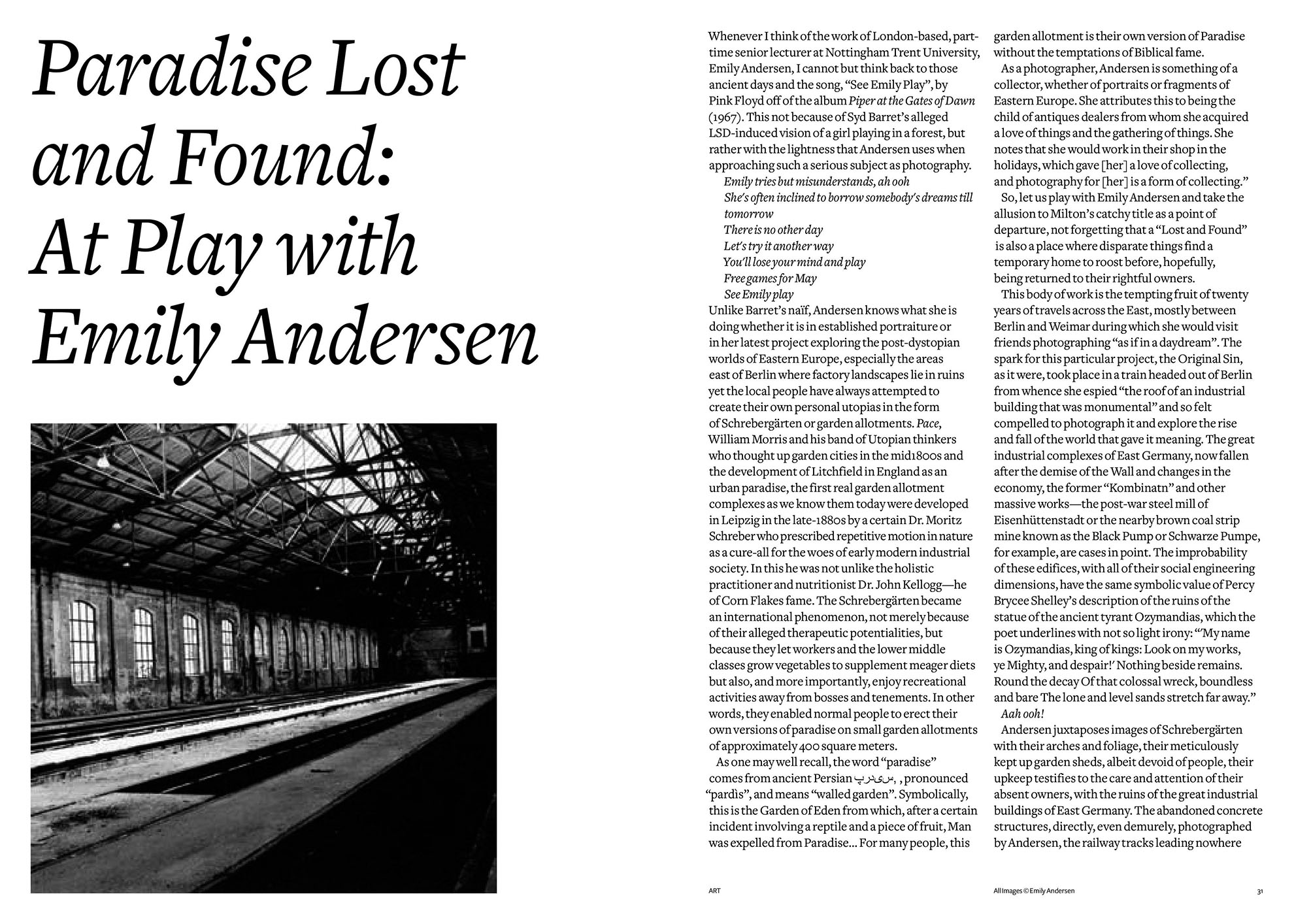

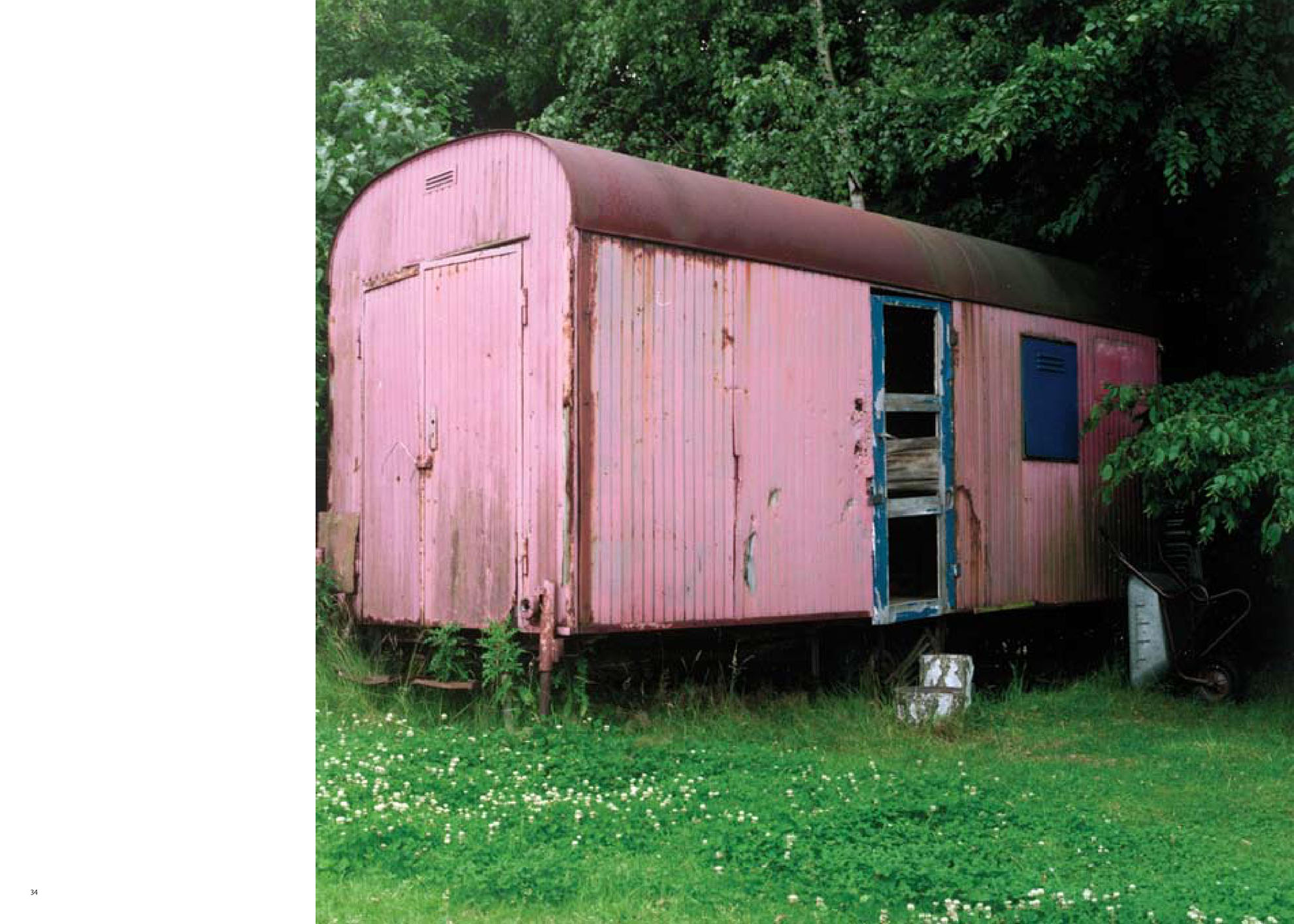

"In former Eastern Germany, Emily Andersen, a London photographer usually associated with portraits, also documented allotments in her book titled Paradise Lost & Found. She explores the universal appropriation of empty spaces and how people create their own 'secret paradises' in sites ignored by passing road and rail travellers. She seeks beauty but not romance in these gardens and in abandoned rundown factories, 'leftovers from socialism's utopian dream.'"

Süddeutsche Zeitung, Photographs by Emily Andersen - A Hidden Paradise, 16 May 2006

"She has chosen a wide-ranging set of subjects: British photographer Emily Andersen's work encompasses portraits, aerial, landscape and architectural photographs. Although Paradise Lost & Found is Ms Andersen's first show in Germany, she has already travelled the country extensively over several years, capturing industrial ruins, allotments or abandoned theme parks with her camera - and thereby uncovering the odd hidden paradise."

Fenella Crichton, Emily Andersen, Black & White Photographs, catalogue, Francis Graham-Dixon Gallery, 1993

(ISBN-10: 1873215657 ISBN-13: 978 – 1873215654)

"Emily Andersen takes photographs of people, often in pairs. Fathers and daughters, mothers and sons act as mirror images or Doppelgängers of one another. Some of them are famous, some unknown. Never emotionally directive in the manner of Diane Arbus, Andersen represents them in natural settings. But unlike the amateur photographer, she is fully aware of the poetry of these interrelationships, of the charged spaces, the articulacy of body language.

One of the most touching images is of Banji Adu and his small daughter, Lily. They stand on the summit of Primrose Hill where three paths converge. He is dressed in a straw hat and black clothes while she, in contrasting white sweatshirt, winds herself round his legs, face towards the camera. He stands like an oak, with her safe below him. At the other extreme, an elderly man sits isolated and stern-faced in front of a formal statue in a German park. Behind him, his adult blonde daughter stands, coat clasped tight, her gaze fixed on another horizon. Behind them both a balustrade suggests a stage. It is as though we were about to witness some terrible Oedipal drama. Some of the sitters are complicit, like Michael Nyman, who sits, Mafia-style, with his two nubile daughters. Others are delightfully natural, like Andersen's own eccentric parents. We all take family snap-shots which we then imbue with the myths borne out of nostalgia. Photographs have no fixed meanings, they are screens on to which we project our versions of the world. What Emily Andersen has understood, with real piquancy, is something of the nature of those fantasies."

Allen Frame on The Body Politic at The Photographers' Gallery, London, 1987 (abridged)

" 'The Body Politic', a group exhibition of photographs at London's Photographers' Gallery, challenges the narrow conventions that prevail in the usual depiction of the human body, gender and sexuality. A dozen photographers present images that defy the stereotypes we are accustomed to seeing. They use a variety of styles and genres, including studio and documentary portraiture, the self-portrait, photo-narrative and arranged photographs. Emily Andersen's documentary portraits of women and their fathers make us realise how seldom women cohabit the same picture frame as men with equality and strength. It is especially refreshing to see young women presented with as much presence and self-assurance as older men, who are the emblems of power in a patriarchal society. In her series of portraits Andersen allows both the men and the women [to express] their individuality. She allows young women [to show] their power and the older men their vulnerability, and finds a range of nuances in between as well. The sitters are revealed with sympathetic clarity, sometimes engaged, sometimes estranged, sometimes sharing a mood or gazing directly, with composure, at the photographer, while the father hovers out of focus at the bar in the background, a telling indication of a problematic relationship."

Waldemar Januszczak in The Guardian on New Contemporaries at the ICA, London, 1983 (abridged)

"[...]The photography section is again thrown away in the corridor leading to the restaurant, although a special mention should be made of Emily Andersen's exquisitely crafted travel picture. It probably shows a day trip to Dorset but it has the parched, nervous tension of one of those hot American states where the postmen always ring twice."